The seeds of international education were sown in the ashes of WW1. A world weary of conflict sought ways to foster understanding and cooperation across borders. In 1924, amidst this yearning for peace, the International School of Geneva (Ecolint), the world's first international school, was founded on the principles of intercultural dialogue and global citizenship. Ecolint would become a crucible for a new kind of education – one that transcended national boundaries and aimed to cultivate a sense of shared humanity.

At the heart of this pioneering endeavour was a history and geography course developed by Paul Dupuy, a visionary who believed that traditional, nation-centric curricula fueled division and prejudice. Dupuy was an academic (a “Normalien”), a “Dreyfusard”, an anti-colonialist and a philosopher. He taught at the international school in his seventies, emphasising global interconnectedness by exploring historical events and geographical realities from multiple perspectives. Instead of glorifying national heroes and national victories, which had been the staple of a propaganda-driven nationalist educational system throughout the 19th Century and the First World War, this international history and geography course (which, in the 1930s, was taught in French only), fostered critical thinking in a way that traditional curricula could not.

Dupuy saw the teaching of humanities not only as an exercise in internationalism but was animated by the notion that such learning should be as concrete and empirical as possible:

We want to exclude all verbalism and mere memory exercise, we want to increase students' contacts with what is real, concrete and directly observable, and through these contacts stimulate their personal activity, accustom them to observation, comparison and generalisation, and through the Socratic method, develop in them the mental faculties which serve to discover and understand”. (Dupuy 1905, p. 222)

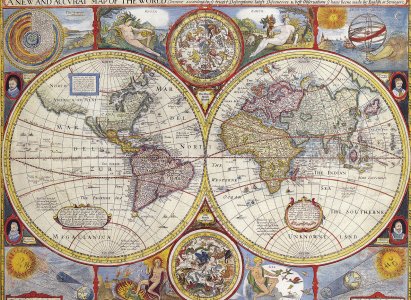

He was against flat maps on walls as he felt that this distorted students' understanding of the true relationship between land masses which could be better understood through the analysis of a globe. This is true since we know that most maps are representationally wrong, either because of the Mercator projection or simply because certain countries are represented as much larger, and others as much smaller, than they really are, essentially for ideological and political purposes. As a result, Dupuy insisted that his students learn directly from globes and not from maps (Dupuy, 1905, p. 228).

Dupuy disliked Atlases for the fragmented picture they would give students, misleading them into seeing the world as separate rather than linked entities. This myth of separation would fossilise misconceptions in young peoples’ minds from an early age, making them conceive of the world in a manner altogether different from reality:

Maps act above all on visual memory and clutter it with recollections whose particular precision creates a general incoherence. Many times have I experienced this myself and I am tempted to believe that the more one is familiar with the school atlas, the more this inconsistency is great. At the very least, terrestrial unity is sacrificed there: the sense of that unity, far from being sparked by repeatedly turning to the atlas, is on the contrary impeded by the constant process of analysis without a common scale - the process on which the creation of the atlas is based. My ambition has been then to bring my students, as I brought myself, to understand and practically sense the earth in its totality, to conceive none of its parts in isolation”. (Oats, 1952, pp. 20-21)

The impact of Dupuy's course was that students were no longer confined to the narratives of their own nations alone; they were exposed to a world of diverse perspectives, challenging their assumptions and broadening their understanding of human experience. Above all, he wanted their first impressions to be accurate, to grapple with the subtleties of actual geographical interrelationships and proportionalities, and for the subsequent mental accommodation that would come to be built on that bedrock of understanding. This was no less the case for history.

Dupuy’s legacy was carried forward by Robert Leach, the brilliant, outspoken, sometimes tyrannical and certainly Quixotic head of history who, from the 1950s right up to the1980s, recognised and continued to promote the transformative power of Dupuy's work. This international approach to the humanities had become particularly salient during the Cold War when history textbooks on either side of the Iron Curtain were imbued with oversimplification and propaganda. Here was a school where, on the contrary, students were learning intentionally about other cultures and histories than their own. Leach took the international humanities course, now taught in both languages, to the "golden triangle" of UK universities (Oxford, Cambridge, and London), to have it recognised as an A-Level, paving the way for its recognition and wider adoption.

The culmination of these efforts was the creation of the International Baccalaureate (IB) in the 1960s. Inspired by the innovative curriculum at Ecolint and driven by a desire to create a globally recognised qualification, the IBDP programme embraced the principles of international education, fostering critical thinking, intercultural understanding, and a commitment to global citizenship. The IB Diploma Programme, with its emphasis on interdisciplinary learning and a global perspective, has become a gold standard in international education, preparing students for a world increasingly defined by interconnectedness and interdependence.

The importance of international humanities education cannot be overstated. There are still countries where textbooks omit the very existence of some countries, maps with inaccurate representations, history books that continue to propagate whitewashed, partial or politically warped narratives. Most history and geography classes still have maps on the walls, and most of the time, these will be distorted representations of what the true geography of space looks like across a globe.

In a chilling documentary, The World's War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire, the historian David Olusoga (who recently addressed Ecolint students and staff) explains how nationalist historians deliberately downplayed the pivotal role African troops played in WW1, literally recreating scenes of the victory of Verdun for film footage so as not to represent the reality of that battle but to give it a more “French” feel. Unpacking such coverups is the work of an historian. This is just one example of how necessary it is to continue to strive for a truthful reconstitution of the past rather than a mindless propagation of oversimplified historical narratives, just as Dupuy wanted his students to see the world as a globe and not a rectangle.

The irony is that when humanities teachers try to do this: to get to the truthful core behind the veneer of representation - which is what a historian should do - when this points to the historical underrepresentation or discrimination of minority groups, they are accused of proselytising, of ideologising the curriculum, of exercising Marxist or Critical Race Theory instead of simply teaching the facts. But what are the facts? That Christopher Columbus discovered America? That Pythagoras invented Pi?

On the other hand, history should not be glazed over as a series of righteous judgements of past Western heroes who are all cast as racists, sexists and ruthless exploiters. Many of them were, some less than others, but trying to reduce the past to a game of oppressors and victims is not entirely accurate either. As an example, statues, references and images of Sir Francis Drake were removed from numerous educational institutions in the UK in 2020 because of his involvement in the slave trade. Labelled as a “pioneer” of slavery, closer and more accurate historical analysis showed that his involvement was indirect and not as active as his detractors claimed in the name of history. This is not to say that he was an angel, but at the same time, much more than a grotesque villain.

History should not be a series of hystericised turf wars through which the past is instrumentalised in order to suit a contemporary political agenda. Unfortunately, this is often what happens.

The only lodestar that should guide us in the teaching of the humanities, is a searching for the truth, even if we never arrive at the truth and even if absolute truth in a Platonic sense might not even exist: the seeking should be for a more accurate representation of human histories and geographies than those that came before. This is what Dupuy wanted and this should remain our goal today.

By exposing young minds to diverse perspectives and challenging them to think critically about global issues, an international humanities education equips them with the knowledge, skills, and values necessary to become responsible global citizens. It empowers them to bridge divides, challenge stereotypes, and contribute to a more peaceful and sustainable future which should be built on a truthful analysis of the past.

In a world grappling with complex challenges like climate change, inequality, and political polarisation, an international humanities education offers a powerful antidote to the division and conflict created by oversimplified Manichaeism.

The founders of international education envisioned a world where education would serve as a bulwark against prejudice, they believed that by fostering understanding and empathy across cultures, education could break down the barriers that, ultimately, lead to war. This vision remains as relevant today as it was a century ago.

Conrad Hughes

Director General

References

Dupuy, P. (1905). Les procédés et le matériel de l'enseignement géographique Annales de Géographie, 75: ppp 222- 233.

Oats, W. (1952). 'The International School of Geneva, an experiment in international and intercultural education', thesis submitted to Melbourne University.