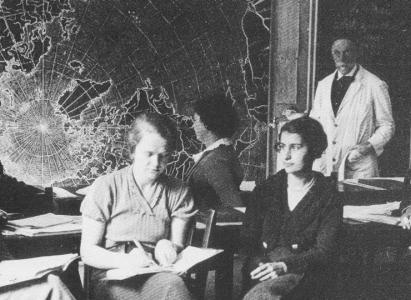

Photo of Paul Dupuy in his "International Culture" class, Ecolint, 1934.

The Ecole Internationale de Genève (Ecolint) is the world’s oldest continuously operating international school. This leads us to discuss what exactly we mean by international school. Is it a school that offers schooling to children of different nationalities? Is it a school that offers an international curriculum? Is it a school specifically accredited as an international school?

Much has been written about the existential questions concerning the identity of international schools. I am not going to draw out that debate here but will say that, to me, the important question that any school calling itself an international school should be asking is precisely that, what does it mean to us to be an international school? What are we doing to be an international school? The term should be less of a technical definition and more a rallying cry continuously to build a culture, curriculum, staffing and general ethos that respond to the most basic tenets of internationalism:

- Recognition of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Teaching and learning across several cultures and nationalities and not simply a national curriculum

- Ongoing critical reflection and action to address global challenges, such as the Sustainable Development Goals

- Understanding specifically international phenomena such as international law, international trade, diplomacy and the complex sociological and economic challenges brought about by globalisation

- Developing intercultural literacy (the understanding of different cultures and the attitudes needed to navigate cultural difference well)

While one of the main early theoreticians of international education from Ecolint was the charismatic, outspoken Marie-Thérèse Maurette, whose UNESCO pamphlets on international education speak of the importance of an education for peace and the learning of several languages, the person who perhaps put theory into practice more patently was her father, Paul Dupuy.

Dupuy taught at the Ecole normale supérieure in France and had a formidable academic grounding in geography, history and mathematics. Astonishingly, at almost 70 years old, he came out of retirement to teach at Ecolint.

Records of him speak of a certain austerity: faded black and white photographs show a gaunt, hard face out of which two fiery, intense eyes stare into you. Dupuy’s striking portrait makes it almost impossible not to imagine someone with a strong personality. In a recent interview I had with Ecolint alumnus and highly accomplished economist Erik Thorbecke, he mentioned how Dupuy would strut up and down the school’s grounds clutching onto a notebook into which he was constantly jotting down ideas. The anecdote says something about the temperament of the man.

Dupuy was famous for his geography lessons. It is important to remember that after the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and World War I, the study of geography was a major vehicle for imperialistic and militaristic nationalism throughout Europe. Dupuy reversed the trend by having students learn international geography. On the wall of his classroom, he had a map of the world drawn from the perspective of the North Pole, to remind students in the early 1930s that questions of location, centrality and position were relative and political. He had students learn about islands in the Pacific and coastlines remote from the habitual lessons they would be receiving in other schools about European geopolitics.

There are also records of Dupuy deriding colonialism publicly, commenting on the absurdity of efforts to deculture citizens of African, American and Asian countries so as to make them second class colonial subjects. Dupuy, like many “Normaliens” (academics linked to the Ecole normale supérieure) at the time was a strong Dreyfusard, deploring the anti-Semitic sentiments at work and lack of fairness that distorted the Dreyfus affair. He was clearly not only a person of principle but well ahead of his time and was not afraid to show it. This deconstructs the lazy argument that past generations were generally more open to human rights abuses because it was an accepted norm: people like Dupuy were active and were not afraid to be openly critical. Indeed, history reminds us that it is often the few, not the many, who will stand up to injustices.

About 30 years later, the international humanities course that Dupuy had created at Ecolint was taken to the London triangle of universities by Robert Leach, inventor of the Model United Nations system. This was to have the course recognised as an A-Level. Ultimately it would lead to a group of schools and educators coming together to create the International Baccalaureate. The seed that Dupuy had sowed would come to grow into an international force throughout the world, which is what the International Baccalaureate is today.

Dupuy reminds us of one important lesson: the mark of an international school is about the critical perspectives you take - and allow to flourish - and the actions you take in the classroom actively to enhance an international approach. For all of us working in international schools, let’s remind ourselves of Paul Dupuy and the work he did almost 100 years ago to promote international mindedness: it is not something that will happen of its own accord or can be expected to emerge spontaneously from a written curriculum, it develops through intentional, deliberate pedagogic interactions.

Note

Some of the information in this article comes from an excellent symposium entitled “Symposium on the origins of international education and on the birth of the International School of Geneva'' held on 1-2 April 2023 and organised by Alejandro Rodriguez-Giovo, Foundation Archivist. I am particularly indebted to Roland Carrupt for his entertaining presentation on Dupuy.