Many readers will be aware of the pop star with the deepest Ecolintian roots, Lori Lieberman (who conceived and first sang one of the most hauntingly memorable pop songs of all time, “Killing Me Softly”). It is perhaps less well known that some years before Lori joined the school, Ecolint had helped to foster another singer who achieved a legendary status in the Francophone world (and beyond). With the help of documents from the 1950s and 60s, Foundation Archivist Alejandro Rodríguez-Giovo sheds light on this notable episode in Ecolint’s musical heritage.

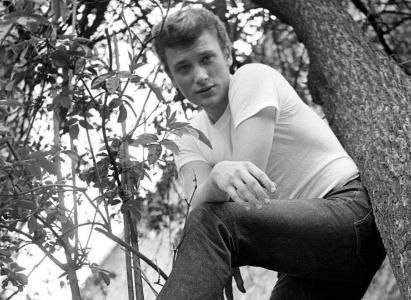

16 February 1963. Salle de la Réformation, also known as the “Calvinium”, where in 1920 the League of Nations, which fostered Ecolint's birth, held its first assembly. This is the unlikely venue for the earliest joint concert in Geneva of the French-speaking world’s hottest duo, 19-year-old Johnny Hallyday (who has just launched rock-and- roll in France) and 18-year-old Sylvie Vartan. Two adolescents accost the pair as they are preparing to leave after the show, with Johnny (already famous for his on-stage athleticism) soaking up his perspiration with a towel. They good-naturedly submit to the teenagers’ persistence and agree to be interviewed in a small, adjoining room.

Johnny Hallyday : C’est bien vous qui me poursuivez depuis hier après-midi ?

Teenager 1 : En effet, comme nous te l’avons déjà dit, nous voudrions une interview pour L’Ecolint Libérée.

J. H. : Bien. Allez-y, posez vos questions.

Teenager 2 : Merci. Tout d’abord, quel est le nombre exact de tes disques et chansons sortis depuis 1959 ?

J. H. : Environ 6 ou 7 millions de disques et une cinquantaine de chansons.

Teenager 2 : D’autre part, on dit que tu t’embourgeoises ; qu’en penses-tu ?

J. H. : Je ne le pense pas, mais à mes débuts, j’avais seize ans, j’en aurai vingt le 15 juin, et il me semble nécessaire de se «calmer» petit à petit si l’on veut arriver à un résultat un peu durable. (…)

Teenager 2 : Et toi, Sylvie, te lances-tu définitivement dans la chanson, ou comptes- tu terminer ta carrière d’ici un ou deux ans en fondant un foyer, par exemple ?

Sylvie Vartan : Cela dépend de tous mes copains. Tant que je plairai, je ne me dégonflerai pas !

Teenager 1 : Certains bruits courent disant qu’il y aurait autre chose que de l’amitié pure et simple entre Johnny et toi ?

S. V. : Oh ! J’aime bien Johnny, mais comme un copain.

Teenager 1 : Mais toi, Johnny, qu’en penses- tu ?

J. H. : (Il rit) Qui sait ? Jusqu’à nouvel ordre il n’a pas été question de mariage entre nous. (…)

Teenager 1 : Si ce n’est pas indiscret, combien gagnes-tu par soirée comme celle-ci ?

S. V. : J’ai touché 3'000 francs de cachet pour chacune des deux.

J. H. : Moi, 10'000 francs, mais il faut soustraire au moins la moitié pour payer orchestre, imprésarios, etc…

Who are these two cheeky adolescents, who grill the famous couple with such chutzpah and subject them to the familiarity of tutoiement (even more impudent in 1963 than it would be today)? And what on earth is L’Ecolint Libérée?

Both of the youths were (you guessed it) Ecolint students at the time: Emmanuel Haymann (Teenager 1, aged 16) and Michel Halpérin (Teenager 2, aged 14), respectively the founder and the editor of L’Ecolint Libérée, a thoughtful, enterprising and witty student magazine. Haymann went on to become a distinguished historian and prolific, prize- winning author, and Halpérin achieved renown both as a lawyer and as a politician, eventually becoming the president of Geneva’s Grand Conseil (parliament).

Seeing how curious Emmanuel and Michel were in 1963 about the nascent stars of Francophone pop music (Johnny Hallyday went on to secure the largest and most devoted following of any French singer – a million people accompanied his funeral on the streets of Paris in 2017), imagine how galvanizing it would have been for them at the time to realize that they had almost overlapped in Ecolint with another young man also destined to become a pop legend in la langue de Molière: Joe Dassin.

Dassin has a reasonable claim to be regarded as the second most beloved pop singer of the Francophone world, after Johnny Hallyday. He sold over 50 million records in his compact 16-year career (he died, romantically but tragically young, in Tahiti). But the comparison between the two idols ends there. Whereas Johnny cultivated a provocative, aggressive, electrifying and strident style that played to a youthful, nonconformist audience, Joe came across as gentle, mellifluous, warm and humane. The good-natured, sensitive content of Joe’s lyrics, combined with the smooth resonance of his voice and the catchiness of his music rendered him irresistible to everyone, regardless of age or cultural background. From the very start, Joe Dassin was adored by all and sundry, de 7 à 77 ans (to employ the famous slogan of the Journal de Tintin at the time).

This fact was brought home to me when I attended his Geneva show in 1971, in the company of Chris Robinson, an Ecolint schoolmate. The venue on that occasion was not the Salle de la Réformation (which had been demolished in 1969) but – almost as improbably – the venerable Victoria Hall, the genevois temple of classical music. Equally improbable (indeed, surrealistic) in that solemn setting was the curtain-raiser to Joe’s performance: trained seals juggling with beach-balls on their upturned noses. The Victoria Hall’s august auditorium was jam- packed with boisterous, enthusiastic fans, but Chris and I – who, like all adolescents, were self-conscious about our image and aspired to be “cool” – were taken aback by the number of young children and their grandparents (or great-grandparents) in the audience. Every age segment of Geneva’s population was, it seemed, proportionately represented, and everyone clapped and sang along to Joe’s hits (or “tubes”, as they’re known in French). It was difficult not to do likewise, given the magnetic sympathie that he irradiated from the stage, as he danced gracefully and rhythmically, dressed in a tight-fitting, immaculate white outfit, in unison with six no less dazzling young women in minuscule mini-skirts.

My friend and I would have been astonished to learn that this demigod whose music so enraptured us had, from 1954 to 1956, studied in the same classrooms as us, with many of the same teachers – despite his fame, no one in the school had ever mentioned this in our hearing. Neither had we the slightest inkling that Joe’s father was Jules Dassin, the celebrated film director, although we had enjoyed his classic, star-studded heist flick, Topkapi (1964). The cinematographic talent of Dassin Sr. – evident in movies such as The Canterville Ghost (1944) and The Naked City (1948), and later in the classic Never on Sunday (1960) – was already widely recognized in Hollywood when he was blacklisted with devastating effect by the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee, on the grounds that he was a communist (with impeccable integrity, Dassin had, in fact, abandoned the Communist Party in 1939, in disgust at the cynical Molotov- Ribbentrop Pact). Systematically excluded from all cinema employment in the USA, he and his wife, Beatrice, and their three children (including Joe, born in 1938), emigrated to Europe in 1952.

My friend and I would have been astonished to learn that this demigod whose music so enraptured us had, from 1954 to 1956, studied in the same classrooms as us, with many of the same teachers – despite his fame, no one in the school had ever mentioned this in our hearing. Neither had we the slightest inkling that Joe’s father was Jules Dassin, the celebrated film director, although we had enjoyed his classic, star-studded heist flick, Topkapi (1964). The cinematographic talent of Dassin Sr. – evident in movies such as The Canterville Ghost (1944) and The Naked City (1948), and later in the classic Never on Sunday (1960) – was already widely recognized in Hollywood when he was blacklisted with devastating effect by the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee, on the grounds that he was a communist (with impeccable integrity, Dassin had, in fact, abandoned the Communist Party in 1939, in disgust at the cynical Molotov- Ribbentrop Pact). Systematically excluded from all cinema employment in the USA, he and his wife, Beatrice, and their three children (including Joe, born in 1938), emigrated to Europe in 1952.

For two and a half years, the long arm of the US authorities ensured the failure of Jules Dassin’s attempts to relaunch his career in Europe, by prohibiting the distribution of any film in which he was involved. As Joe’s Ecolint file reveals, the Dassins led a peripatetic existence in France, finally opting to enrol Joe and his two younger sisters as boarders in La Grande Boissière – a natural choice since 1924 for those seeking a haven from religious, racial or political persecution for their children. However, with no reliable source of income, the Dassins soon struggled to keep up with the tuition, board and lodging fees. Although Ecolint was (and, of course, still is) a non-profit school, and as a rule adopted a sympathetic and accommodating attitude towards parents facing financial difficulties, these fees were its only source of revenue, so the situation unavoidably gave rise to exchanges of awkward correspondence.

In July and August of 1955, both Mr. and Mrs. Dassin wrote to P. H. Pol-Simon, Ecolint’s co- director at the time, requesting some form of financial support, specifically for one of their daughters, who stood out academically and “adores the school,” as Mr. Dassin put it. Eventually an arrangement was reached whereby the girl’s fees would be settled not at the beginning of the academic year, as was usual, but at the end, following the release of the first film Jules Dassin had been allowed to direct in Europe: Rififi. (Fortunately, it was an instant success, hailed by critics and still regarded as a landmark film noir).

In parallel, Joe’s behaviour at school was giving his parents some additional headaches. Though charismatic and obviously bright, his independent-minded approach to discipline occasionally brought him into conflict with Ecolint’s authorities, notwithstanding the school’s relatively relaxed and lenient approach to such matters. During the Boarding House’s ski holidays in the Alps, accommodation for boys and girls was pointedly provided in separate establishments. However, during one such holiday, Joe (aged 17) managed surreptitiously to book himself into the young ladies’ pension, ensuring that this room was adjacent to that of his girlfriend at the time. There he was discovered in flagrante delicto and promptly evicted by the hotel’s management. This led to another difficult exchange of correspondence with Mr. and Mrs. Dassin.

With hindsight, given the dozens of charming – and often movingly tender, sensitive and compassionate – songs that Joe dedicated to women during his meteoric career as a pop star (see, for example, “Et si tu n'existais pas”, “C’est la vie, Lily”, “La demoiselle de déshonneur” or “Je la connais si bien”), such incipient romantic escapades seem eminently forgivable. No singer could have been further removed from hard-nosed, condescending and demeaning macho lyrics and postures (which were far from uncommon then, and sadly still are). One can’t identify with certainty every influence that contributes to shaping an individual’s sensibilities, but it’s plausible to assume that Ecolint’s values played a positive role during Joe’s formative years, encouraging him to find within himself the empathy for the feelings of others that came to characterize his work.

No one who listens to “Le Portugais,” which Joe composed in collaboration with his sister Richelle in 1970, will fail to be struck by this empathy. The song touchingly explores the perspective of Portuguese migrant workers, who – long before European Union membership brought prosperity to their country – all too often had to exile themselves to support their families. Attitudes towards them in the host countries were not very different from those that today are encountered by migrants or refugees from Africa and the Middle East. In 1970, it caused quite a stir that a mainstream pop star at the zenith of his success should devote his talent to such a subject. To affirm that Joe Dassin consciously lived his life in the light of Ecolint’s ethical standards might be a far- fetched claim; but, as his track record (no pun intended) shows, he did implement his virtuosity and allure in a manner that fosters respect and affection between all human beings, and promotes justice and joy – in short, in the Ecolint way.

This article was originally published in Echo magazine, issue n°26, summer 2021.